A discussion article by a Free Our Unions supporter, reposted from the original here.

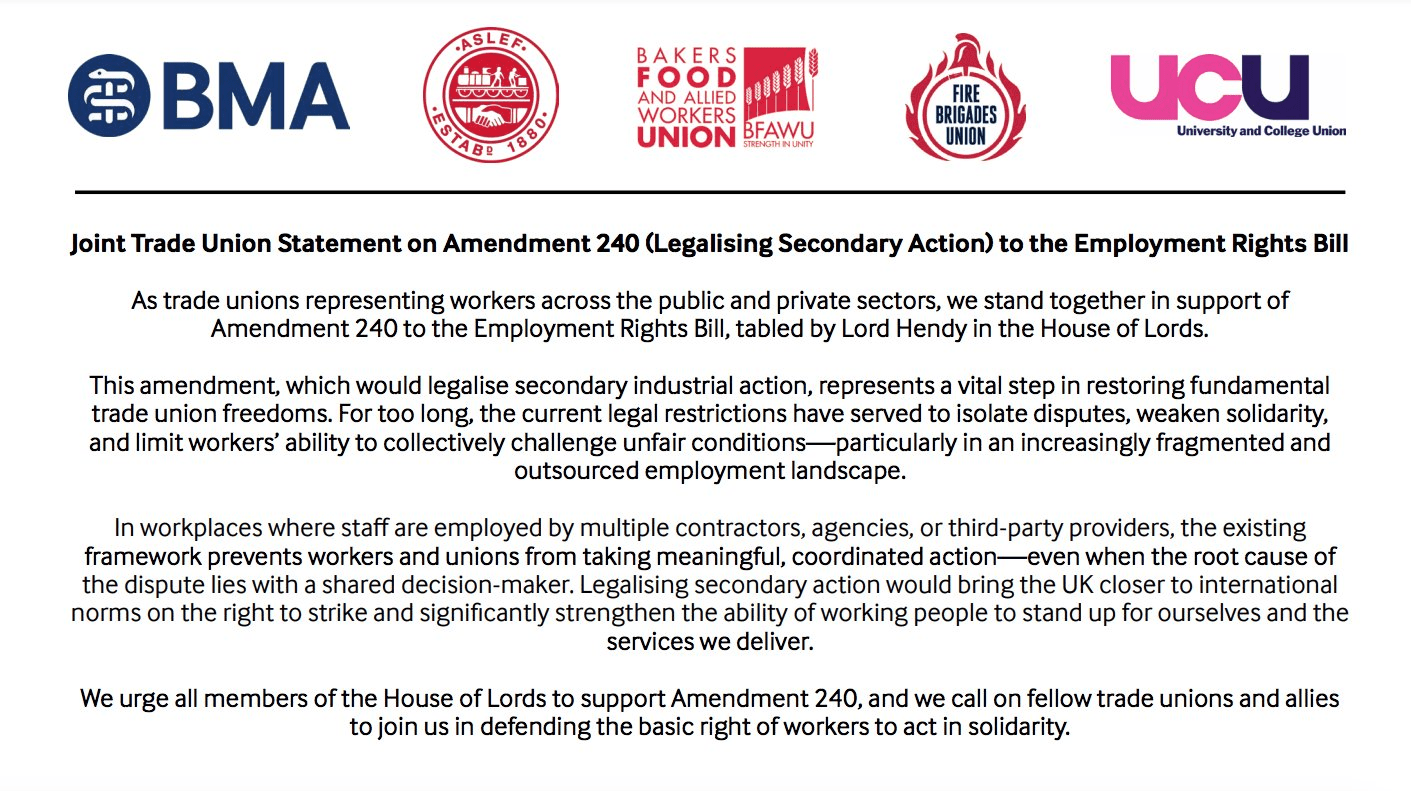

On 9 June five trade unions – BMA, FBU, ASLEF, BFAWU and UCU – put out a joint statement calling for the ban on solidarity strikes to be repealed.

The hook was an amendment to the government’s Employment Rights Bill in the House of Lords, proposed by a left-wing Labour peer, the employment rights lawyer and campaigner John Hendy. (PCS also put out a statement in support of Hendy’s amendment, but for some reason did not sign the joint one.) Suspended Labour MP Zarah Sultana tried to put a similar amendment in the Commons but was unable to do so.

Hendy eventually withdrew his amendment to avoid heavy defeat. Its submission did allow a brief flow of campaigning. Trade unionists and socialists must work to make this the start of ongoing and wider campaigning.

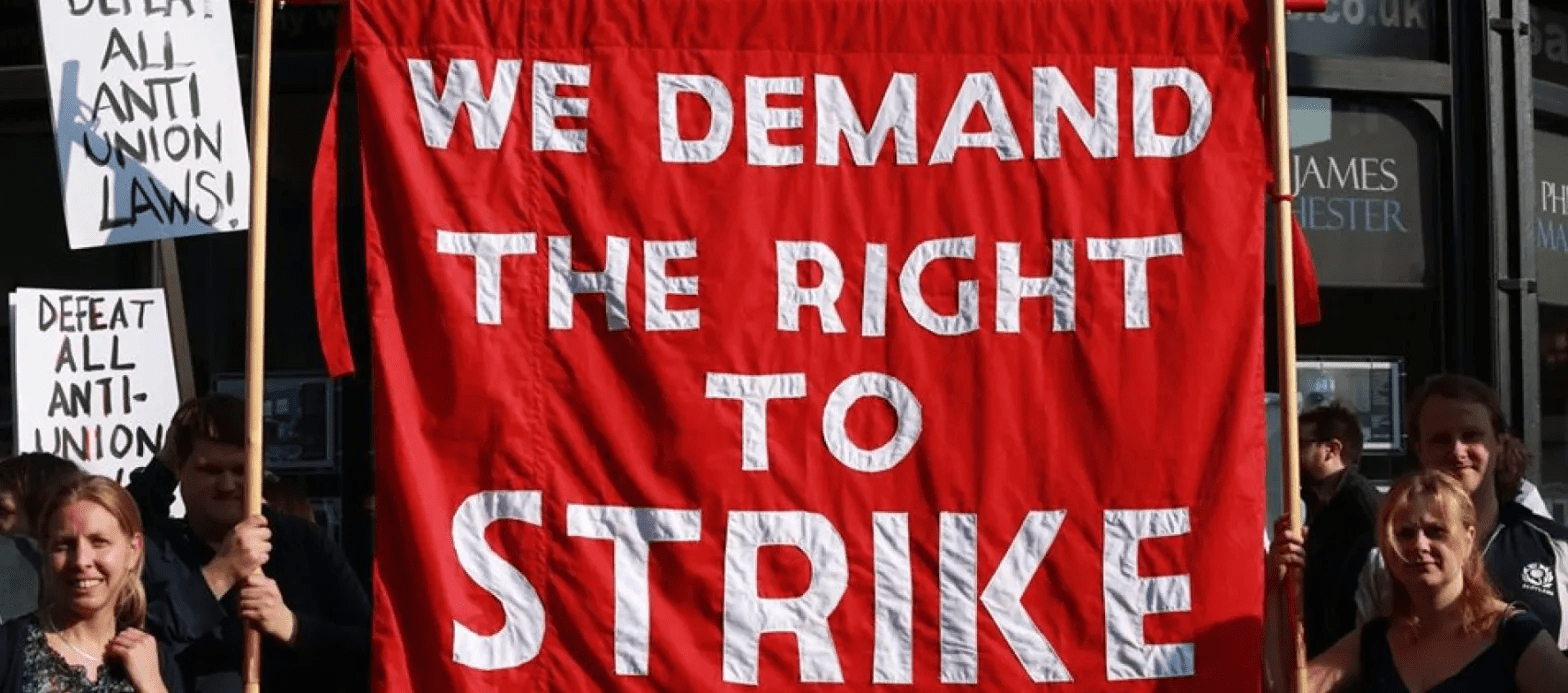

The Institute of Employment Rights, of which Hendy is part, has rightly called the ban on “secondary action” – denying workers the right to strike and picket in support of those working for another employer – an affront to and attack on “the whole ethos of the labour movement”.

The right to take solidarity action was restricted in Thatcher’s first anti-union laws (the 1980 and 1982 Employment Acts). Despite these restrictions, legal strikes in solidarity with NHS workers’ disputes took place on a large scale in 1982 and a still significant scale in 1988. In recent years, when workers without much knowledge of the history or the law raise the idea of solidarity strikes, it seems to almost always be in connection with NHS workers’ disputes…

In 1990 the last Thatcher government outlawed solidarity completely.

Overturning the ban has never been a priority for the labour movement – but absolutely should have been and still should be. It has increased practical importance in an era when privatisation, outsourcing and other forms of fragmented employment have made it common for workers in the same workplace to be employed by different employers, in fact or as a legal fiction.

In 2017-20, during Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership of the Labour Party, the Free Our Unions campaign raised this issue as part of its wider agitation for repeal of the anti-union laws, working closely with the Fire Brigades Union in particular. (See here for a briefing on Hendy’s amendment.) Unfortunately while leading the Labour Party Corbyn and co. generally evaded the issue, and the Institute of Employment Rights, then acting as semi-official advisers to the leadership, increasingly downplayed it.

During this period numerous union conferences, and TUC Congress, passed policy for repeal of all anti-union laws, specifically citing the ban on solidarity action. And yet it seems likely that part of what explains the reticence of the Corbyn leadership is hostility on the party of trade union leaderships to the demand, even in unions where conferences had voted for repeal of all anti-union laws.

For conservative union leaders and bureaucrats, even ones who see themselves as on the left, repealing recent restrictions like the 2016 Trade Union Act and the 2023 Minimum Service Levels law is one thing; repealing older anti-union laws, thus shifting a significant degree of power from the bureaucrats effectively responsible for administering them back to the rank and file, is quite another.

There have been reports that when legalising solidarity action was raised with the Labour Party during its 2024 discussions with affiliated unions on the Employment Rights Bill, representatives of UNISON (ie of its right-wing senior leadership and bureaucracy) hurried to squash the issue.

Hendy should be congratulated for putting forward his amendment to the Bill (along with other strengthening amendments he proposed). But, typically, the IER and its associated “Campaign for Trade Union Freedom” did nothing to campaign around the amendment – not even to the extent of social media posts.

Campaigning was driven primarily by leading reps in the British Medical Association (BMA) who have connections with Free Our Unions. It was they who pulled the BMA as an institution into action, got other unions on board and organised online agitation, for which immense credit.

Limited as it was, this was the biggest agitation focused on this issue since 2005, when unions raised it in the Labour Party after the Gate Gourmet dispute: defeating Blair at Labour Party conference, but building no ongoing campaign and quickly letting the issue fade away.

On the other hand the agitation around Hendy’s amendment could easily have been multiplied many times over if others had done more to help BMA comrades. The weaknesses of the IER have already been mentioned. Similarly the potentially very important UNISON left did little to help. But the problem was general, across the labour movement. It did not help that the BMA statements and publicity came out just before Hendy’s amendment was up, giving little time to build campaigning; but that was far from the only difficulty.

With the amendment withdrawn, the Employment Rights Bill will not overturn the ban on solidarity action. Fighting to do so should be an important part of the further and much wider campaigning to strengthen trade union rights that will be desperately needed after the Bill is passed.

Jo Sutton-Klein, a Manchester doctor and BMA Council member who was central to this campaigning, told me:

“Workers coming together with other workers is at the core of trade unionism, and is how many improvements to our pay, conditions and safety at work have been won. The restriction preventing workers joining in solidarity with other workers beyond their immediate employer has significantly weakened our ability to fight back against falling pay and safety at work.

“Going forward trade unionists need to become better educated on trade union law, where it comes from, and how it is enacted in their workplace and union, both so they can better challenge it when it is being enforced by union bureaucrats and employers, and so we are better placed to change the law.

“It is also worth noting that although out-and-out solidarity action is currently unlawful, there are still de facto forms of solidarity which aren’t: notably coordination and synchronisation of ballots and strikes. Despite the fact we saw ballots and strikes across many sectors during the 2022-3 strike wave, there haven’t been any significant attempts by unions to synchronise ballots. We could have had one big ballot of education, transport, healthcare and other sectors and a coordinated strike essentially turning the strike days into bank holidays – but union leaderships have been very reluctant to make this happen.

“Trade unionists should seek to get better at organising their workplaces, and seek ways to coordinate action, including through synchronised ballots and strikes across different sectors. We should also educate colleagues about the possibilities and consequences of wildcat strikes, and how difficulties might be mitigated.”