The government is backtracking on its promise to repeal the 2016 Trade Union Act – now saying that repeal of the crucial 50% turnout threshold for strike ballots will be delayed indefinitely, until after electronic balloting is introduced.

Whether or not it’s strictly true to say, as some have, that Labour promised to remove the restriction within a hundred days (as opposed to introducing legislation within a hundred days), this is clearly a violation of the spirit of its promise as understood by the labour movement.

Even more importantly, it is a move to keep the unions fully shackled for a potentially long period. A period, not coincidentally, in which the government intends to introduce a new wave of austerity in the public sector.

It’s unclear whether the delay also applies to removal of the other threshold the Trade Union Act introduced, of 40% of all eligible members voting yes in “important services” – health, fire, pre-17 education, border security, nuclear and transport.

A group of union leaders has protested publicly against this backtracking and called for campaigning to reverse it. Rank-and-file activists and branches need to step up pressure for this call to be put into action.

Among other things, we should mobilise within our unions to push them to organise a protest and lobby at Parliament, which then TUC President Matt Wrack called for last year, but which was not taken up by the unions.

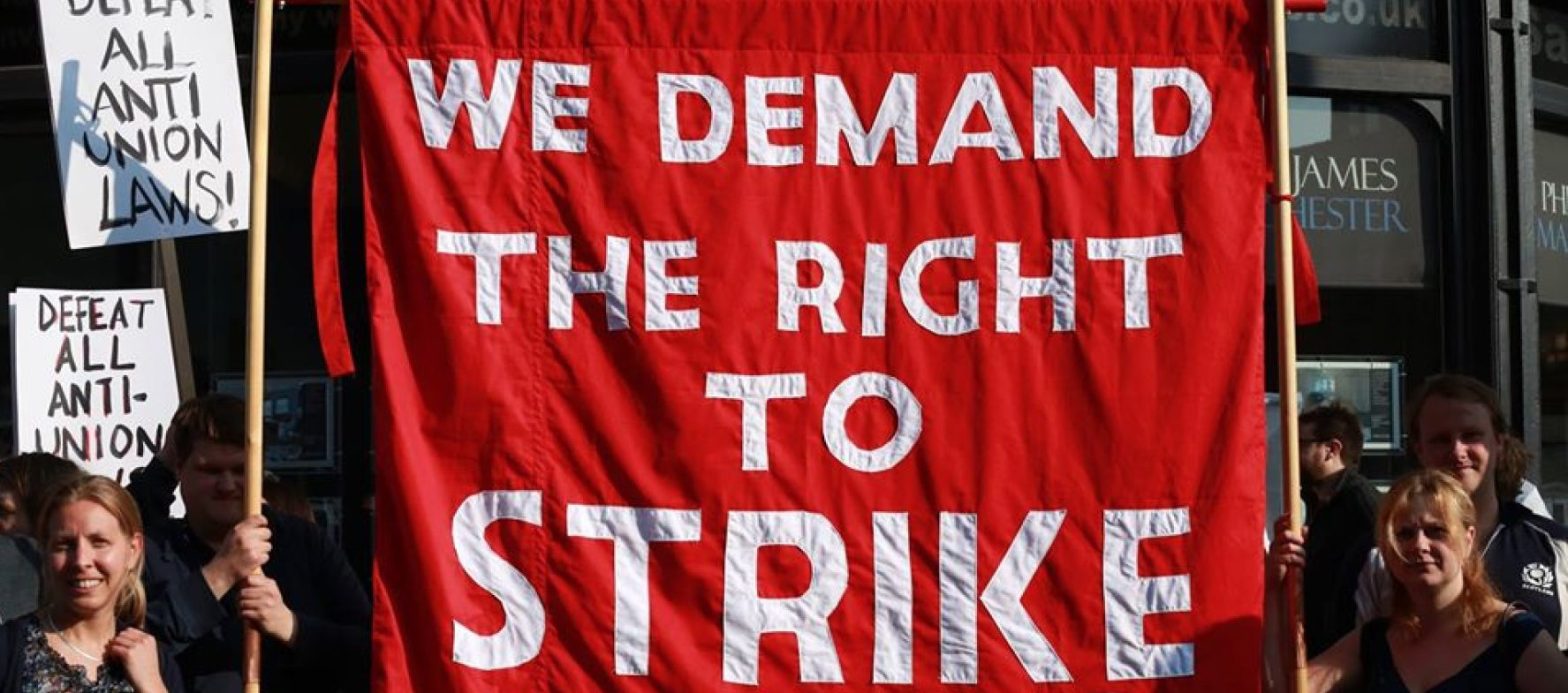

We need, and Free Our Unions will continue to campaign, to go far beyond the provisions of the Employment Rights Bill, to win repeal of all anti-trade union laws, back to 1979, and their replacement with strong legal rights for workers and unions, including strong rights to strike and picket. Workers need the right to strike at a time, by a process and for demands of their choosing, including in solidarity with other workers and for political as well as industrial demands, and to picket freely.

But, immediately, the labour movement should fight to strengthen the Bill, including by holding the Labour government to its promises – in letter and spirit.

We encourage supporters to submit this motion to their union branches:

Notes:

1. The government’s backtracking on various aspects of workers’ rights.

2. That this includes the pledge made immediately before the election to introduce workplace balloting as well as electronic balloting for strikes; and now an indeterminate delay in repealing the 50% turnout threshold introduced by the 2016 Trade Union Act (until after electronic balloting is introduced).

3. That many union leaders have protested publicly about the delay in repealing the 50% threshold, and called for campaigning to reverse this decision.

Believes:

1. That we need to go far beyond the provisions of the Employment Rights Bill, to win repeal of ALL anti-trade union laws, back to 1979, and their replacement with strong legal rights for workers and unions, including strong rights to strike and picket.

2. That, immediately, the labour movement should fight to strengthen the Bill, including by holding the Labour government to its promises.

Resolves:

1. To call for strengthening of the Employment Rights Bill, including holding Labour to it promises in letter and spirit.

2. To call for the 50% turnout threshold to be repealed immediately on the passing of the Bill into law.

3. To connect with other branches to organise campaigning on this issue, including pushing for the union to call action, including demonstrations, at national level.

4. To invite a speaker from the Free Our Unions campaign to address a future meeting.